How 236,471 words of amici briefing gave us the 565 word Gonzalez decision

The behind the scenes story of how legal realism and Supreme Court incompetence led to a false-five-alarm fire

There has been a lot said about Gonzalez v. Google, the first Supreme Court Section 230 case in 22 years. Of course, in those 2+ decades Section 230’s “twenty-six words that created the internet” have generated their fair share of courtroom and political controversy. But even given 230’s lightning-rod status for free speech and the internet, interest in the Gonzalez case was extreme. Experts and interest groups filed a total of 78 different amici in Gonzalez alone1, totaling 236,471 (!!!) words for Google and 470,002 words total. In light of the volume, the Court extended oral arguments to 70 minutes and then still blew through that time limit by an hour and 34 minutes.

With so much to say, one might think there was much to be said, that is until two weeks ago, when the Court dismissed the case in a perfunctory 2.5 page per curiam opinion that was brief enough to fit into a 15 Tweet-thread.

Doesn’t that make you go, “hmmm?”

That sure is a lot of words and time for. . . . not a lot of words and time. Indeed, I think FAR more interesting than anything you could read about the legal issues discussed in the thousands of pages of briefing or ignored in the breviloquent final decision, was the delta in word-count between them, which belied a two-year long narrative arc of legal realism2.

Let me take you back to April 2021

The story, such that it is, begins in April of 2021 when Justice Clarence Thomas issued a very odd concurrence on a procedural dismissal of the case which had successfully challenged then-President Trump’s ability to block users on Twitter under the First Amendment. That case (confusingly called Knight v. Biden in the dismissal because of the change in administrations, but originally called Knight v. Trump) had since been rendered moot when Trump lost the election and ceased to be a government official.

With no live issue, the Court had little to do except clear the matter from the docket, which it did: granting cert, vacating the judgment, and remanding for dismissal in three tidy sentences — which made the multi-page Thomas’s concurrence attached to it all the weirder.

The concurrence had the vibe of an unprovoked rant, with Thomas harnessing many of the far-right conservative ideologies around the censorship of Big Tech companies, championing the controversial idea of applying common carriage doctrine to internet platforms, and attacking Section 230. But perhaps most concerning for internet law experts who disagreed, was that Thomas seemed to be essentially putting out a call-for-cases. “It’s an invitation for plaintiff’s lawyers to bring cases challenging Section 230,” Jeff Kosseff, an internet law professor and author of the authoritative book on the controversial law, said at the time. “And I would not be surprised if we would start seeing more states passing laws that attempted to regulate content moderation.”

Skip forward to one year later in April 2022

Kosseff turned out to be prescient on both fronts. Less than a year after Thomas’s writing, in early April 2022, lawyers for the plaintiff in Gonzalez filed for writ in the Supreme Court, challenging the application of platform immunity in Section 230.

But few law and technology experts had the time to take note of the case because Kosseff’s second prediction had also come true: both Florida and Texas had passed laws in 2021 putting in place must-carry-like provisions for social media.

So in the Spring of 2022, just as Gonzalez and its companion case Taamneh v. Twitter wound their way to the Supreme Court, almost no one was looking. Instead, all eyes were on the 11th and 5th Circuit Courts which were issuing dramatically divergent opinions on the Florida and Texas laws under the First Amendment. These cases -- Netchoice v. Moody (Florida) and Netchoice v. Paxton (Texas) -- were not only raising big Constitutional issues, they had generated a circuit split, both of which made the odds of them being granted cert in the Court both high stakes and high probability.

October 2022: Everyone’s hair is on fire with the Netchoice cases and then the Supreme Court sets their feet on fire with Gonzalez and Taamneh

So when the Court announced on October 3, 2022 that it was granting cert in two relatively unknown, and low-profile internet tort cases, internet law experts were caught on their back foot. “When we were surprised by the cert grant, there was a sense that we [the internet law experts] might have just really misunderstood or underestimated the strength of these two cases,” said Mike Godwin, an internet law expert who filed an amicus brief in Gonzalez. But as many dropped everything to get up to speed on Gonzalez and Taamneh, another possibility emerged. It was not that these cases were underestimated in their legal strength or facts, which with the specter of Thomas’s activist concurrence, made the concern far greater. Instead, “as we dug in, we could see that the cases didn’t seem likely to provide the Court an easy way to reinterpret Section 230,” Godwin recounts, “unless the Court was dead-set on reaching that result regardless of what the underlying issues might be.”

It’s worth noting here that internet law lawyers don’t spend a lot of time in the U.S. Supreme Court. As I mentioned above, the last major case heard by the Court was Reno v. ACLU in 1997, which struck down all but Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and set the stage, for better or worse, for the next two decades. Now, suddenly, in the span of a few weeks, there were two cases granted and two more likely to be granted in the coming months.

“There’s a very turbulent legal landscape ahead,” Daphne Keller, an internet lawyer at Stanford Cyber Policy Center summarized in an interview at the time. “It’s like Dobbs, in that everyone feels the law is up for grabs, that justices will act on their political convictions and would be willing to disregard precedent.”

The issues in the Netchoice cases were huge and complex -- First Amendment, dormant commerce clause, and federalism -- but now the threats of Gonzalez and Taamneh were direct and imminent. Over the next several weeks lawyers and advocates working on these issues scrambled to weigh in. The result of the five alarm fire translated into a huge flood of amicus briefing -- 47 in support of affirmance or Google, 18 in favor of reversal or Gonzalez, and 13 supporting neither party (Full disclosure: I signed onto a brief with other law professors and law and tech experts in favor of Google).

The Farcical February Oral Arguments

By the time oral arguments rolled around in late February of this year, there was a mix of collective exhaustion and massive pessimism. Though I knew many who trekked to DC to wait in a line for 19 hours in the cold to attend oral argument in person, most of us were relegated to listening from the public audio feed provided for the Court. I organized group of experts to listen and weigh in via liveblog at the Rebooting Social Media Institute at Harvard, where I was a fellow -- most people were excited for the camaraderie, but more than one declined reasoning that “given the odds we’ll be witnessing firsthand the demise of the internet” they preferred to be alone.

Supreme Court oral arguments are historically not a great predictor of the outcome of a case. Sometimes topics that come up at great length in discussion never even are discussed in the final opinion and the moods of the justices are hard to read and often change. So the group of us that assembled -- a mix of lawyers and legal types who had followed closely or filed briefs in the case -- gathered that morning with low expectations that we would learn anything new and a sense of gallows humor. If the internet was going to die that day, at least we’d be hanging out in Slack together making memes when it happened.

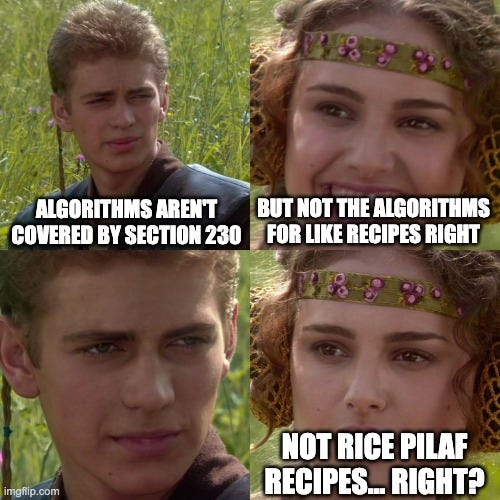

But as arguments began, it was clear that something very far outside the normal was happening. As the plaintiff, Gonzalez’s attorney went first, and at the close of his opening statement, unsurprisingly given his presumed interest in the case, the first question was from Thomas. But oddly the question from Thomas seemed somewhat hostile to the plaintiff’s arguments, urging him to make a better case: “I think you have to give us a clearer example of what your point is exactly,” the Justice stated, offering a few examples of what results one might get from asking a YouTube algorithm for a recipe of “rice pilaf from Uzbekistan . . .you don't want pilaf from some other place, say, Louisiana.”

But whether for nerves, or ineptitude, the plaintiff’s attorney seemed unable to clarify his arguments to satisfy Thomas or really any of the justices, even as they tried to offer him help in doing so. As they went through their questions, it seemed not a single justice could tell why they were hearing this case and what the plaintiff was arguing for . . . and they were confused in nine different ways:

“Does your position send us down the road such that 230 really can't mean anything at all?” asked Justice Kagan.

“I -- I don't know where you're drawing the line. That's the problem,” said Alito, later adding “I'm afraid I'm completely confused by whatever argument you're making at the present time.”

“Can we back up a little bit and try to at least help me get my mind around your argument about how we should read the text of the statute?” offered Justice Jackson.

“Can I break down your complaint a moment?” asked Justice Sotomayor, summarizing the plaintiff’s main claim, then in a question that would turn any attorney’s blood cold asking, “I think, as I'm listening to you today, you seem to have abandoned that.”

Over at our little live blog the funereal mood had turned into an almost jocular one. Slowly a new possibility about what the Court’s decision to hear arguments in Gonzalez and Taamneh emerged: maybe the Court had wanted to take an internet law tort case, but they’d picked badly and they now they knew it.

Resolving these cases in favor of the plaintiffs wouldn’t just radically re-interpret Section 230, it would also dramatically re-write the law on what “aiding and abetting” meant under the law -- and that would have ramifications on all of tort law, not just social media. In other words, maybe the Court had been willing to be little activist, but not this activist.

How do you solve a problem like a Mistaken Grant of Cert?

So over on the live blog we started contemplating: maybe this isn’t end times for internet, maybe this is just an accident. What do you do with a Supreme Court case that you f*cked up in hearing? Well, if the Court wanted to resolve their little accident with as little damage as possible it had two best options. The thing a Court can do when it grants something seemingly on error is to “deny as improvidently granted.” As the arguments continued to deteriorate, Supreme Court expert, law professor Steve Vladeck, floated this as a possibility on Twitter.

The other option, as Ben Wittes of

pointed out in our liveblog and in the Lawfare Podcast, was to rule for Twitter in the companion case to Gonzalez, and then use that resolution to avoid having to rule in Gonzalez at all. That, at least, would save the Court face, but to the same general effect.And that is precisely what happened.

In Taamneh, a unanimous Court wrote a relatively brief 30 page opinion that upheld the dismissal of a case against social media companies. That decision made way for the less than 600 word per curiam in Gonzales, where the Court “declined to address” the issues raised in the over quarter of a million words of amicus briefs written on the case.

And that, bunnies, is how the Supreme Court turns a quarter-million words into 565

With such an unceremonious conclusion, many might see all those words from friends of the Court as wasted. After all, most people consider amicus briefs successful when they appear as cited in a majority opinion, not when they collective generate a barely 3 page dismissal. But as part of this broader story of the case, it's the best possible outcome.

“All the amicus work was vindicated,” Keller texted me minutes after the decision was released, “precisely by being made to seem so unnecessary.”

K.K.P.S.

For paid subscribers only: An etymology that really shocked me and I am going to remember to impress people at cocktail parties; a funny TikTok of my adventure morel hunting with Scott Shapiro; my mom’s recipe for Ranch Oyster Crackers; predictions on the Ted Lasso finale and this poll to vote in (genuinely interested in the results and/or will fight you about them in comments).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Klonickles to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.