The Anti-TikTok Law

An explainer on the law and politics around the controversial new TikTok regulation.

On April 24, President Biden signed into law what most people are calling the TikTok Ban. Not to be an obnoxious lawyer about it, but it is really more accurate to call it The Anti-TikTok Law, because deciding what the law is — a ban, a forced divestment, a forced divestment that is so difficult to achieve that it is effectively a ban, etc. — is what is going to be at the heart of the litigation that started last week when TikTok filed suit and what happens to that app on your phone when the divestment deadline hits on January 19, 2025.

There’s a bunch of questions to unwind to know how to answer those questions. Today we’re going to walk you through them.

First of all, how did we get here?

The attempts to ban TikTok actually began in late 2019, when the Defense Department’s labeled the app as a security risk, which prompted the U.S. Army and Navy to ban TikTok on their issued devices. Then in the summer of 2020, President Trump issued three executive orders forcing TikTok’s parent company ByteDance to divest its ownership of TikTok or else be banned from U.S. operations (these were never made good on).

When President Biden took office in 2021, he promptly repealed all of these orders by Trump, but he did sign the ‘No TikTok on Government Devices Act’ in late December 2022. Similar laws banning TikTok from state employees’ phones proliferated in the following year in mostly Republican and some Democratic states. Montana went so far as to pass a ban on TikTok on all personal devices, but this ban was blocked from taking effect by a federal judge citing constitutional issues in late 2023 (litigation is still pending in that case).

Since then, something new has prompted Congress to finally take the possibility of a nationwide TikTok ban seriously, and all signs point to increased pressure from constituencies concerned about the antisemitic speech that has spiked across the web since the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war in October.

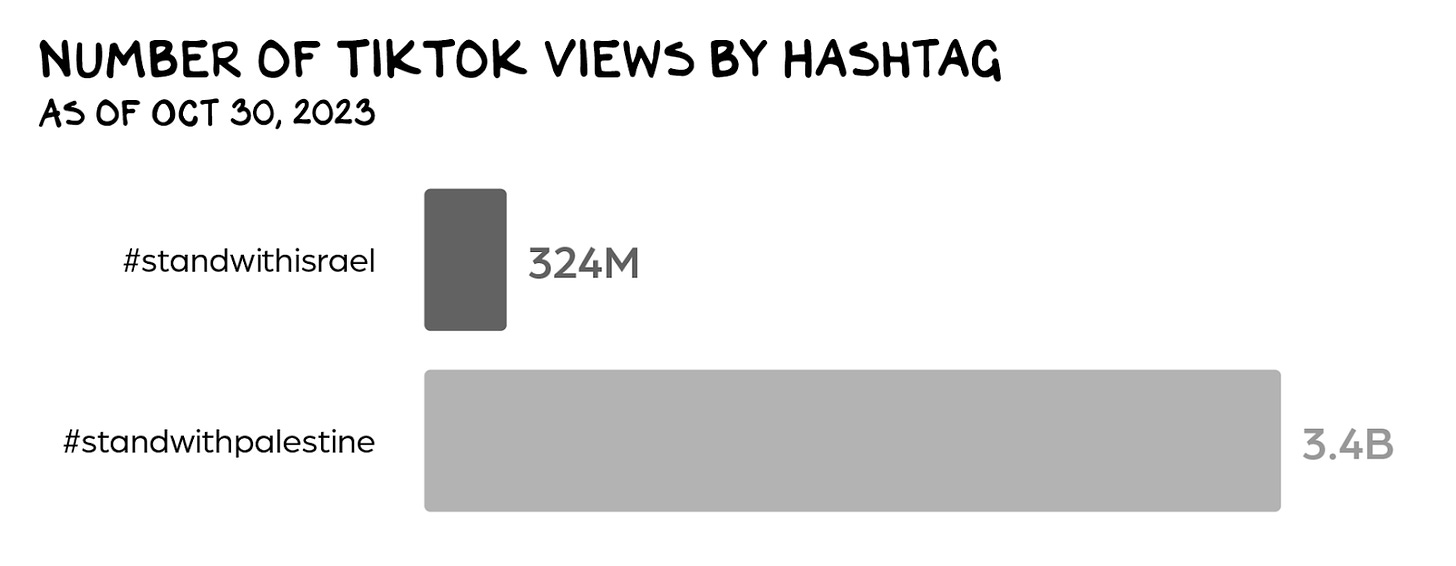

While hate speech saw a surge across all social media platforms, Chinese ownership of TikTok prompted particular scrutiny of the platform’s content moderation and recommendation systems. A search of the number of TikTok views by hashtag indicated that pro-Palestine content was getting more views (like, more than 10x more views) than pro-Israel content, for example.

Of course TikTok has vehemently pushed back against allegations that it fuels antisemitism, claiming that the popularity of content is simply reflective of user preferences. But this didn’t stop the tide that was already underway in Washington.

The GOP-led House passed a ‘divest or ban’ bill in March 2024 — which at the time was not expected to pass the Senate (I wrongly predicted that it wouldn’t in a previous round-up). But then at the last minute it was attached to an amended version of the much-delayed bill to send a $61b aid package to Ukraine and $26b to Israel and Biden signed it into law on April 24, starting the 270 day (9 month) clock that ByteDance (TikTok’s Chinese parent company) has to divest in TikTok in the U.S. market.

So is it a ban, or what? How does divestment even work?

Ok, so now we have this Anti-TikTok Law. Let’s call it the Anti-TikTok Law (for now) because deciding what the law is — a ban, a forced divestment, a forced divestment that is so difficult to achieve that it is effectively a ban, etc. — is actually going to be at the heart of the litigation that started last week when TikTok filed suit.

Because a ban would invite the highest level of constitutional scrutiny, sponsors of the bill have unsurprisingly been loath to characterize it as such.. "What we're after is — it's not a ban, it's a forced separation," Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-WI) told NPR. "The TikTok user experience can continue and improve so long as ByteDance doesn't own the company."

But of course, one could argue that if divestment is simply not possible in the 270 day timeframe (antitrust review alone, often takes longer than nine months!) forced divestment just is a de facto ban.

Indeed, there are three reasons that Chinese divestment of TikTok isn’t really feasible:

1. It’s really difficult to find a buyer.

There’s no Elon Musk that can buy TikTok -- the company is much much bigger than Twitter. Outside sources have valued TikTok at somewhere between $50-100 billion, while ByteDance has given an estimate over $225 billion. This narrows the pool of contenders to either the biggest fish in the pond or some combination of US investors . . . and of course either option would have to get through FTC scrutiny during an era of leadership that is notoriously anti-Big Tech — which would likely rule out the likes of Microsoft, Alphabet, Meta for antitrust concerns. In a deal of this scale, the antitrust review process alone would likely take over six months. It’s just not realistic.

2. It’s difficult to actually untangle TikTok from its parent company, ByteDance, and to know when they’re untangled enough.

ByteDance and TikTok are very intertwined. Frankly, it seems like they’ve only become more so in the years since regulators started to push for separation.

Like most transnational tech platforms, its not as if TikTok just has operations or staff in the U.S. — they’ve got teams in Singapore, the UK, Brazil, Germany, South Africa, Australia, and China. According to their petition challenging the suit, TikTok says that complying “with the law’s divestiture requirement, [TikTok’s] code base would have to be moved to a large, alternative team of engineers — a team that does not exist and would have no understanding of the complex code necessary to run the platform.”

Even if separation is possible on this timeline, it would still be hard to know how separate is separate enough. This is especially true given that there’s still no access to the classified intel that convinced Congress to pass this bill.

3. Finally, China simply doesn’t want to divest.

ByteDance owns TikTok’s recommendation algorithm, which the CCP has classified as a sensitive technology. Under China’s 2017 National Security Law, the government would have to approve any export of the algorithm. In March, a spokesman for China’s Ministry of Commerce said the US should “stop unreasonably suppressing” TikTok, adding: “The relevant party should strictly abide by Chinese laws and regulations.” This comment was taken by ByteDance executives as further confirmation from Beijing that ByteDance will encounter regulatory obstacles imposed by the CCP if it attempts to offload TikTok.

“Since 2020 and again in recent months, official Chinese voices have railed against a potential divestment,” write China tech experts Nick Frisch and Dan Wang an op-ed in today’s New York Times. “China’s leaders gain little from permitting a sale. The party is not especially concerned for the interests of ByteDance’s financial investors (who are mostly global institutional investors), nor does Beijing seem to mind an opportunity to jerk the leash of ByteDance. . .”

So this quickly turns into issues of national-sovereignty and global politics: A government can force a divestment in that they can use their power to levy a consequence significant enough to reasonably hope or expect it will prompt the action they desire. But it has now become sufficiently clear that the U.S.’s ‘stick’ — ie. threat of a ban — is not a significant enough consequence to prompt China to sell TikTok to a US owner. Moreover, as Frisch and Wang point out — after years of the U.S.’s sanctimonious defense of a free and open internet, China is loving this moment of hypocrisy.

So if the Anti-TikTok Law is functionally a ban, what will that mean?

There is precedent on banning foreign-owned communications technology. Until 2013, the FCC enforced a rule which imposed a statutory limit on direct foreign ownership of a broadcast license — capping it at a 20% stake in US radio or television stations. Rupert Murdoch, for example, gave up his Australian citizenship and became an American citizen in 1985 in order to exceed the 20% cap and purchase Metromedia.

But banning a social media company like TikTok is a very different thing from capping foreign ownership of a TV station. Online user-generated social media platforms like TikTok are just different in kind from broadcast television and radio, where government regulation is justified based on scarcity of spectrum. Other kinds of media such as newspapers, websites, or online platforms like TikTok don’t have this spectrum issue. You can have an infinite number of newspapers or blogs — at least theoretically — but you can’t have an infinite number of radio stations because of the physical limits of the medium.

And the difference in kind between social media platforms like TikTok and broadcast television and radio aren’t just technological — they’re democratic. Television and radio are few-to-many broadcast mediums: a small number of elite players set an editorial agenda for a small number of channels and publish their media to the masses. But social media and internet technology is a many-to-many broadcast mediums— it isn’t a small amount of curated content sent out to everyone, it’s user-generated content with every viewer also having potential to be a speaker.

While virality and visibility might be controlled by recommender and content moderation systems, its media content is almost entirely private individual speech broadcast to the masses. Millions of Americans are already on TikTok — and are on TikTok as both speakers and listeners. There’s a strong argument in TikTok’s favor that banning the platform would thus unlawfully restrict the speech rights of users themselves — making it in violation of the First Amendment.

So when the deadline hits on January 19, 2025 does that mean I’m suddenly not going to be able to use TikTok?

It’s possible! But if I had to wager a guess its very unlikely given how this litigation will likely go.

As mentioned, TikTok has filed suit saying the law is unconstitutional (for a lot of reasons besides the First Amendment, but the First Amendment is their strongest argument). I would say the case has near zero chances of resolving before January 2025, primarily because the court will see it as not ripe (a legal term for not yet ready for adjudication because its final outcome is contingent on future events) and want to see what happens with the divestment.

In the meantime, as we approach that date, the judge will likely issue a stay preventing the law from going into effect until the question of the litigation is resolved. . . and then it’ll be many more months of litigation, argument, briefing, appeal that we all have to look forward to.

More reading!

For those interested in this, here’s who we’re reading and talking to as we follow along with all things Anti-TikTok Law:

Jameel Jaffer at Columbia’s Knight First Amendment Institute has a great statement summarizing the speech issues with this law.

Anupam Chander at Georgetown University Law Center has a very good Twitter presence (and BlueSky if that’s your flavor) on this stuff and also has written some quick takes on the data privacy and speech issues on Medium.

Nick Frisch and Dan Wang, Chinese tech experts at Yale gave a great run down of how all this is playing out in China’s political agenda.

Great article. Best and most-concise summary of the issue I have seen.

One note: Maybe I have this backwards, but shouldn’t TV/Radio be characterized as “few-to-many” rather than the other way around?

Thanks!

Well-written, excellent, article.